Chinese Art

Wednesday, February 4, 2015

Shitao

Portrait of Ren'an in a Landscape

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707) Zhang Ziwei (Chinese, active late 17th century)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Date: dated 1684

Culture: China

Medium: Handscroll; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: 22 15/18 x 53 7/8 in. (58 x 136.8 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1987

Accession Number: 1987.149

Bamboo in Wind and Rain

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Date: ca. 1694

Culture: China

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Dimensions: Image: 87 3/4 x 30 in. (222.9 x 76.2 cm) Overall with mounting: 132 1/4 x 37 3/8 in. (335.9 x 94.9 cm) Overall with knobs: 132 1/4 x 41 in. (335.9 x 104.1 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1984

Accession Number: 1984.475.2

Shitao, one of the most outstanding landscape masters of his time, was also passionately in love with bamboo painting. On this monumental work, he quotes a description by Su Che (1039–1112) of Wen Tong (1018–1079), the Northern Song bamboo painter: "He dallies amid bamboo in the morning, stays in the company of bamboo in the evening, drinks and eats amid the bamboo, and rests and

sleeps in the shade of bamboo; having observed all the different aspects of the bamboo, he then exhausts all the bamboo's many transformations."

Accompanying Shitao's signature is his seal, which quotes a saying by Wen Tong: "How can I live one day without this gentleman!"

During the eighteenth,century, Shitao's style of bamboo painting was practiced by members of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou.

sleeps in the shade of bamboo; having observed all the different aspects of the bamboo, he then exhausts all the bamboo's many transformations."

Accompanying Shitao's signature is his seal, which quotes a saying by Wen Tong: "How can I live one day without this gentleman!"

During the eighteenth,century, Shitao's style of bamboo painting was practiced by members of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou.

Hermitage in Mount Lu

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Culture: China

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Dimensions: Image: 37 5/16 x 19 11/16 in. (94.8 x 50 cm) Overall with mounting: 76 1/4 x 26 in. (193.7 x 66 cm) Overall with knobs: 76 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. (193.7 x 74.9 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1980

Accession Number: 1980.426.4

Landscape Painted on the Double Ninth Festival

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Date: dated 1705

Culture: China

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: Image: 28 3/16 x 16 5/8 in. (71.6 x 42.2 cm) Overall with mounting: 86 1/8 x 23 in. (218.8 x 58.4 cm) Overall with knobs: 86 1/8 x 26 3/4 in. (218.8 x 67.9 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1981

Accession Number: 1981.285.13

Shitao painted this landscape for a young friend who visited him on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month—a festival traditionally celebrated by mountain climbing. Suddenly struck by his own old age, Shitao wrote this inscription:

The days when I go climbing are few now and my walking staff no longer helps me. . . . When you were young, I was already in my prime; but suddenly, you are a man and I am old. The passage of time plays tricks on people; like mist or the moon, it cannot be trusted. The future is like a cloud or traces of decaying grass—how can one fathom it?

(trans. Wen Feng)

Shitao's painting is like a fleeting vision glimpsed through fog. As the fog lifts, an approaching skiff heralds the arrival of Shitao's friend, whose coming has the effect of clearing weather on the spirits of the housebound artist. Filling the sky above, Shitao's dedicatory poem is written in a buoyantly rhythmic version of "clerical" script. The monumental characters, engraved on stelae or cliff faces, boldly defy the transient imagery of the landscape and bespeak Shitao's determination to achieve permanence through his art.

The days when I go climbing are few now and my walking staff no longer helps me. . . . When you were young, I was already in my prime; but suddenly, you are a man and I am old. The passage of time plays tricks on people; like mist or the moon, it cannot be trusted. The future is like a cloud or traces of decaying grass—how can one fathom it?

(trans. Wen Feng)

Shitao's painting is like a fleeting vision glimpsed through fog. As the fog lifts, an approaching skiff heralds the arrival of Shitao's friend, whose coming has the effect of clearing weather on the spirits of the housebound artist. Filling the sky above, Shitao's dedicatory poem is written in a buoyantly rhythmic version of "clerical" script. The monumental characters, engraved on stelae or cliff faces, boldly defy the transient imagery of the landscape and bespeak Shitao's determination to achieve permanence through his art.

Met Collection

http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/49177

Outing to Zhang Gong's Grotto

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Date: ca. 1700

Culture: China

Medium: Handscroll; ink and color on paper

Dimensions: Image: 18 1/16 x 112 3/4 in. (45.9 x 286.4 cm) Overall with mounting: 18 7/16 x 363 11/16 in. (46.8 x 923.8 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1982

Accession Number: 1982.126

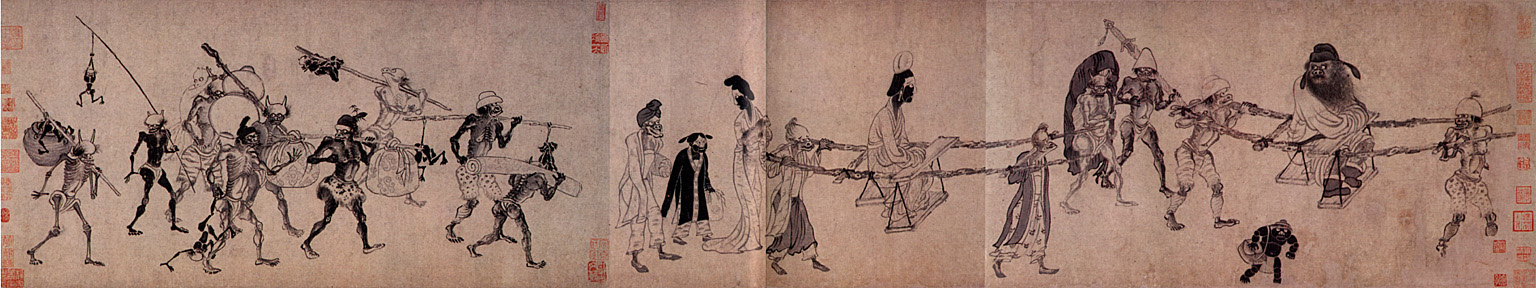

The Sixteen Luohans

Artist: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707)

Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Date: dated 1667

Culture: China

Medium: Handscroll; ink on paper

Dimensions: Image: 18 1/4 x 235 3/4 in. (46.4 x 598.8 cm) Overall with mounting: 22 5/16 x 895 in. (56.7 x 2273.3 cm)

Classification: Paintings

Credit Line: Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1985

Accession Number: 1985.227.1

Shitao, born Zhu Ruoji, a scion of the Ming imperial family, escaped death in his youth by taking refuge in the Buddhist priesthood. In 1662 he became a disciple of the powerful Chan (Zen) master Lü’an Benyue (d. 1676). In the late 1660s and 1670s, while living in seclusion in temples around Xuancheng, Anhui Province, he taught himself to paint.

In The Sixteen Luohans, Shitao’s earliest major extant work, the young painter, then twenty-five, drew what are possibly the most effective figures since the Yuan period (1279–1368). A rare religious subject for Shitao, known for his visionary landscapes, the scroll depicts the sixteen guardian luohans (saints) ordered by the Buddha to live in the mountains and protect the Buddhist law until the coming of the future Buddha.

Stylistically, the immediate sources for Shitao’s figures were late Ming painters, such as Ding Yunpeng (1547–ca. 1621) and Wu Bin (act. ca. 1583–1626). Unlike Wu Bin’s luohans, which seem to be merely grotesque caricatures, Shitao’s are carefully observed, showing such thoroughly human qualities as humor and curiosity.

In The Sixteen Luohans, Shitao’s earliest major extant work, the young painter, then twenty-five, drew what are possibly the most effective figures since the Yuan period (1279–1368). A rare religious subject for Shitao, known for his visionary landscapes, the scroll depicts the sixteen guardian luohans (saints) ordered by the Buddha to live in the mountains and protect the Buddhist law until the coming of the future Buddha.

Stylistically, the immediate sources for Shitao’s figures were late Ming painters, such as Ding Yunpeng (1547–ca. 1621) and Wu Bin (act. ca. 1583–1626). Unlike Wu Bin’s luohans, which seem to be merely grotesque caricatures, Shitao’s are carefully observed, showing such thoroughly human qualities as humor and curiosity.

Artist / Maker / Culture

Object Type / Material

Geographic Location

Date / Era

Department

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

Bodhidharma

An exhibit of Zen Buddhist paintings on Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism in China is on display at the Beijing Museum of Visual Art. A total of over 50 pieces from Li Zhi, a Zen painting master from the Shaolin Monastery and a member of the China Artists Association, are on display through Nov. 24. According to Li, the concept of Zen involves the pursuit of harmony between mankind and nature.

http://www1.chinaculture.org/classics/2013-11/19/content_496086_19.htm

http://www1.chinaculture.org/classics/2013-11/19/content_496086_19.htm

Saturday, December 13, 2014

Monday, September 8, 2014

Lady Wen-chi's Return to China +

Lady Wen-chi's Return to China

Attributed to Li T'ang (ca. 1049-after 1130), Sung Dynasty

Album leaves, ink and colors on silk, 50.7 x 39.7 cm

This album is composed of 18 leaves in a format in which the text is above and the illustration below, forming a continuous sequence for the story. It narrates the story of the gifted Eastern Han lady Ts'ai Wen-chi, who during a period of chaos in the early 3rd century was captured by nomads and married off to King Tso-hsien of the Southern Hsiung-nu. Not until 12 years later was she ransomed and then escorted home by Ts'ao Ts'ao.

Each illustrated segment is descriptive in terms of the details of the story, the figures, horses, and background scenery. Originally attributed to the Sung court painter Li T'ang, the painting here dates slightly later stylistically. Damaged in places, it was restored by a Ming dynasty (1368-1644) painter.

http://www.npm.gov.tw/english/exhbition/epla0104/b/main04.htm

Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute (Chinese: 胡笳十八拍; pinyin: Hújiā Shíbā Pāi) are a series of Chinese songs and poems about the life of Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE) poet Cai Wenji, the songs were composed by Liu Shang, a poet of the middle Tang Dynasty. Later Emperor Gaozong of Song (1107–1187) commissioned a handscroll with the songs accompanied by 18 painted scenes.

Poet and composer Cai Yan, more commonly known by her courtesy name "Wenji", was the daughter of a prominent Eastern Han man of letters, Cai Yong. The family resided in Yu Prefecture, Chenliu Commandery, in what is now eastern Henan Province. Cai Wenji was born shortly before 178 CE, and was married at the age of sixteen according to the East Asian age reckoning (corresponding to the age of 15 in Western reckoning) to Wei Zhongdao in 192 CE. Zhongdao died soon after the wedding, without any offspring.[3] 194–195 CE brought Xiongnu nomads into the Chinese capital and Cai Wenji was taken, along with other hostages, into the frontier. During her captivity, she became the wife of the Zuoxianwang ('Leftside Virtuous King' or 'Wise King of the Left'),[4] and bore him two sons. It was not until twelve years later that Cao Cao, the Chancellor of Han, ransomed her in the name of her father, who had already died before her capture. When Cai Wenji returned to her homeland, she left her children behind in the frontier.

Historical sequel

Anonymous painting of Cai Wenji and her Xiongnu husband (Zuoxianwang) dated from the Southern Song Dynasty (文姬归汉图). They are riding their horses along, each holding one of their sons. The expression on Cai Wenji's

face appears rather fulfilled, peaceful and content, while the husband

was turning his head back in farewell (transl. by Rong Dong)

Cai Wenji departure from China. One of the scrolls in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy of the Photo Library Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[2]

Abduction' of Cai Wenji. Nomads armed with bows and their mounts have two different forms of horse-armour (14th century painting replica of 8th century original, Metropolitan Mus., Dillon Fund 1973.120.3, NY)[1]

Chinese allegorical devices, as defined by Erich Auerbach,[9] are "something real and historical which announces something else that is also real and historical...the relation between the two events is related by an accord or similarity".[10] There are obvious parallels between Cai Wenji's story and that of Gaozong's mother, the Empress Dowager Wei (衛太后), who was captured along with the rest of the imperial clan and held hostage in the north. She was not released until a peace treaty was concluded between the Song Dynasty and the Jurchens in 1142.[11] Despite its allegorical development derived from Cai Wenji's story, her image today reverberates primarily with the feeling of sorrow.

- Attila and the Nomad Hordes (Elite) by David Nicolle and Angus Mcbride (2006) p.46

- Maxine Hong Kingston's The Woman Warrior: A Casebook (Casebooks in Contemporary Fiction) by Sau-ling Cynthia Wong (1998) p. 109

- Hans H. Frankel Cai Yan and the Poems Attributed to Her Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, Vol. 5, No. 1/2 (July, 1983), pp. 133–156

- The 5th. Dimension: Doorways to the Universe by Aona (2004) p.249

- Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang by Christian Tyler (2204) p.29

- The Oxford Book of Exile by John Simpso (2002) p.11

- The C.C. Wang Family Collection of Important Early Chinese Works of Art (Hardcover) by Sotheby's (1990)

- Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute: The Story of Lady Wen-Chi by Robert A. Rorex (1974) Robert A. Rorex, Wen Fong (1975) Metropolitan Museum of Art ISBN 0-87099-095-0, ISBN 978-0-87099-095-3

- Figura by Erich Auerbach, Trotta (2000) ISBN 84-8164-229-0

- Michael Holquist, Erich Auerbach and the Fate of Philology Today, Poetics Today, Vol. 20, No. 1 (1999), pp. 77–91

- Hong Mai's Record of the Listener And Its Song Dynasty Context (S U N Y Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture) by Alistair David Inglis (2006) p.26

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighteen_Songs_of_a_Nomad_Flute

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)